Revised 02/09/2020

Geometry of a 3 Sided Bowl

This page will explore the geometry of a 3 sided bowl turned from a block of wood.

Why? Knowing about its geometry allows one to plan a turning before it is placed on the lathe. This may enable

the turner to make better use of the wood including the ability to make more than one item from the block.

This page is divided into the following sections:

Part 1: The Analysis

The analysis uses some very simple math all of which taught or used in high school geometry courses.

Lets look at what is used for the sake of anyone who has forgotten what they learned in their geometry

and earlier math classes.

- Square roots. For example, the square root of 9 is 3 because 3 squared is 9. We will use the notation

√9 = 3. We will do the algebra for you so you can

follow the work even if you have forgotten how to manipulate square roots. But if you are interested, you may recall

√ab =

√a√b,

√a/b =

√a/√b and

√a2 = a. Typically we avoid writing

square roots in denominator. This can be done by a technique called rationalize the denominator.

1/√a = (1/√a) x (√a/√a)

= √a/a

- The Pythagorean theorem. It applies to right triangles with a 90o right angle. It states that

the square of the length of the long side, called the hypotenuse, equals the sum of the squares of the

lengths the two shorter sides. If we

use c for the length of the hypotenuse and a and

b as the lengths of the other 2 sides, the mathematical notation for

this rule is

c2 = a2 + b2

or

c = √a2 + b2.

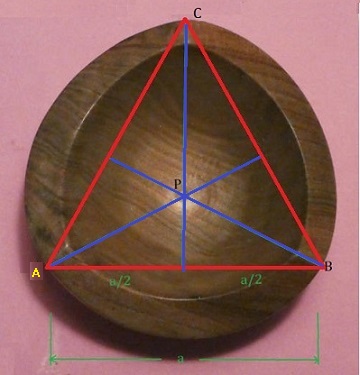

- Equilateral triangles. Equilateral triangles are triangles with 3 equal sides. If you look at the

picture on the left

which is the top view of a 3 sided bowl, you can see why they are relevant. We see the red lines connecting

the 3 corners of the bowl form an equilateral triangle which has some very helpful

properties. The corners, called vertices of the triangle are denoted by

A, B, and C.

The blue lines are perpendicular (right angle) to the red lines and meet at point P,

the so-called center of the triangle.

These lines bisect the corresponding red lines dividing them in half. The lines from

P to the vertices are called

circumradii. If we denote the length of the sides by a, the length of a

blue line (called an altitude) is a√3/2

and the length of a

circumradius (like PC) is 2/3rds of that length, namely

a√3/3.

One last comment. We say the equilateral triangle is

inscribed in the circle formed by the outside of the bowl.

If desired, you can review the properties of equilateral triangles in web pages such as

https://brilliant.org/wiki/properties-of-equilateral-triangles

or even

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Equilateral_triangle.

- Similar. In geometry similar objects have the same shape. One is just an enlargement of the other.

In the figure on the right, the red and blue figures are similar and the linear dimensions are proportional. Thus,

if a, b, c, and

d are lengths of their sides, then a/b = c/d.

-------

Turning a normal 3 sided bowl is fairly a standard technique that does

not require any special knowledge of its geometrical properties. But

knowing some may allow advanced variations of this shape

and/or more economical use of the cube allowing one to turn multiple objects from

the same cube.

Consider Figure 1 shown on the left. A cube with edges of length

s is shown. Five of its eight

vertices (corners) are marked V, V',

A, B, and C.

We would place the cube in the lathe using the opposite vertices

V and V' and the

dashed line becomes the center line about which the cube is rotated. Then vertices

A, B, and C

are in a plane perpendicular to the center line axis of rotation. This

plane is outlined in red and lightly shaded. A,

B, and C are the three vertices closest

to vertex (corner) V.

Using the Pythagorean theorem

(c2 = a2 + b2),

we can determine that the length of the diagonals

such as the lines AC, AB and

BC across sides of the cube have length

s√2, that is, s times

the square root of 2. Using the theorem a second time one can determine the diagonals between

opposite vertices such as between V and V'

have length s√3, that is,

s times the square root of 3.

Now let us assume that we cut the cube along the plane containing the vertices

A, B, and C.

The result is shown in Figure 2. The boundary lines are shown in red as in the previous figure. These lines are

diagonals of a side of the cube and we have determined their length is

s√2.

Because all of its sides have equal lengths, the triangle ABC is an equilateral

triangle.

One of the basic properties of equilateral triangles says that if you draw the vertical line though

C, it will bisect the line AB, so each

half of the base has length s√2/2.

If we draw the same lines through vertices A and B,

the equilateral triangle

properties say that all of the lines will meet at one point P, the "center" of the triangle.

That point is significant as it is on the line that is the center of rotation for the entire blank. Applying some more well

known properties of equilateral triangles, we find that the lines from point P to the

vertices have length s√6/3.) (You check this out

using the normal formulas for an equilateral triangle, remembering each side of this triangle has length

s√2.)

That means that the theoretical radius of 3 sided bowl is

s√6/3 and its diameter is

2s√6/3. This ignores any rounding of the corners,

sanding, or off centering when placing the cube or the parts in the lathe.

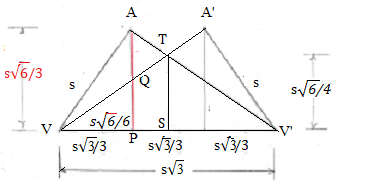

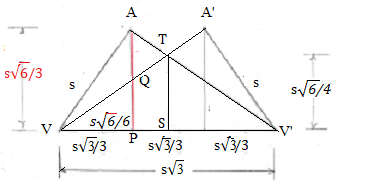

Now that we have the radius and diameter of the bowl, we turn to the horizontal spacing of the vertices and Figure 3.

A word about that sketch. The upside down "W" shape is top half the shape that one would see when the cube is

turning on the lathe.

Actually vertices A and A' never line up. If vertex

A is on top, then turning the cube 60o

or 180o would bring vertex

A' to the position shown. Or you may think of the lines

VA'and A'V' as being the inverted bottom half

of the cube which is not shown in Figure 3.

A spinning cube

We know the hypotenuse of the right triangle with vertices V,

P, and A has length

s and the vertical line side through A has length

s√6/3. Using the Pythagorean theorem again,

we determine that the bottom

of the triangle has length s/√3 or equivalently

s√3/3.

By symmetry, the other end at V' has the same length. That is neat because each is 1/3 of the length

of the line between the vertices. So the distance between the vertices A and

A' is also the same! That means we have the two most important measurements

for the 3 sided bowl.

We will now get one more measurement that might be useful. We will determine the radius of the blank at its

midpoint - its "waist". That is where the two sloped lines meet at T. We observe that

the two right triangles VQP and VTS are similar - they have

the same shape even though they have different sizes. The sides have the same ratio. Thus,

QP/VP = TS/VS. Substituting and simplifying gives

TS = s√6/4. The diameter of the blank at that point is twice that or

s√6/2.

Unfortunately because of the square roots, some people may find these formulas difficult to use.

An Excel like spreadsheet in Dimensions of 3 Sided Bowl provides a convenient

table of calculations for various sized cubes.

Go to top of page

Part 2: Using the Analysis

We have three examples, showing how the formulas in Part 1 can be used to help

by showing the feasibility of turning 3 sided bowls in a given cube and how the part

or parts can be arranged. In each case, multiple items are turned from a single

cube of wood.

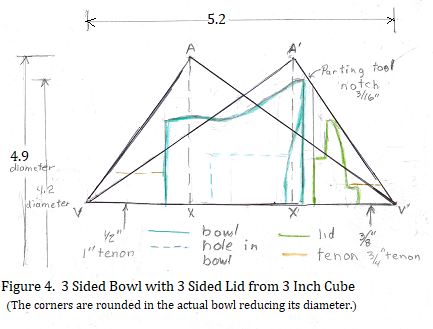

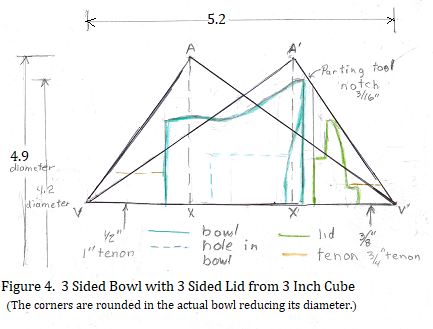

Example 1: This is the example that motivated the study of the geometry of 3

sided bowls. Before starting on this bowl, I wanted to know if it was indeed possible

to turn a bowl and lid from the same cube, and if so, how to organize the parts. An

additional problem was the available cube was only 3 inches on each side. The

formulas for the bowl length, vertex spacing and radius of the points allowed me to

make a full sized drawing like the one shown in Figure 3 and graphically answer

those questions. Figure 4 shows the top half of the block with bowl turned on its

side as it would be in the lathe. I found that I could use 1 inch diameter (1/2 inch

radius) tenon for the bowl and a 3/4 inch diameter (3/8 inch radius) tenon for the lid.

Fortunately, I have a set of #1 jaws for my 4-jaw chuck because it would not have

been possible to turn the bowl in such a small cube using the more standard #2 jaws.

The #1 jaws can grip the small diameter tenons that were used. The tenons are rather

long to help prevent the bowl or lid from flying out of the jaws. The lid handle was

turned from the lid's tenon after the lid was pulled part way out of the jaws. The top

fits into a 1-1/2 inch hole drilled with a sequence of forstner bits.

Example 2: Another question was "Is it possible to turn 2 bowls from 1 cube?"

It turns out that it is possible although the resulting bowls are so shallow, it might be

better to call them "saucers". Figure 5 shows the 2 saucers facing each other. The

layout includes notches for the parting tool used to separate the bowls. Prototypes

were turned from a very small cube about 2-1/2 inches on a side. The Prototypes

proved the possibility although I broke a corner off the second bowl and it turned out to

be circular bowl instead. Both bowls are less than 1 inch in height.

Figure 6. Two bowls and a lid from one 4 inch cube

Example 3: While working on the analytics of 3 sided bowls, it occurred to me that it

would be possible to use an alternate arrangement of the bowls and even include a lid

for the one of the bowls. As shown in Figure 6, the two bowls are oriented in the

same direction instead of facing each other. The drawings showed that at least a 4

inch cube would be needed. The two bowls are not identical. It is doubtful that one

could turn this arrangement without planning using the analytical formulas. Getting 3

items from 1 cube is pretty economical use of the wood.

Update: I hadn't had time to try this example when this page was originally written. Now

I have and the result is shown above. The pieces were turned from a 4-1/2 inch cube. Actually this

was a double experiment. It was turned from a cube constructed of pieces of 1/4 inch

plywood underlayment glued together. There was some problems with the plywood

delaminating. If you look carefully, you can see one corner of the left piece in the picture

(which was the right hand piece in Fig. 6) is missing.

I would probably try to use better plywood in the future. I didn't

follow the plan exactly. But it shows that the idea would actually work. Moreover,

the shallower bowls are easier on one's fingers during the turning and sanding process than

a deeper, standard 3-corner bowl. The lid looks better than

the bowl used in Example 1. Another picture of the bowl with one piece used as a stand is

shown in this picture.

Hint to anyone who tries this. When turning 3 cornered bowls form a cube made of plywood,

significant and parts of the top and bottom face may show up in the bowls. This was particularly

true in this 3 part set as can be seen in the above picture. Make sure the top

and bottom are nice before gluing. Stack the plywood

pieces to see how high the cube will be and cut the squares a little larger than that height.

After gluing you will have to trim the sides but hopefully not the top and bottom to make a cube. Sand

the sides to make them smooth before turning. Sanding the surfaces before turning is much

easier than sanding the flat surfaces after turning.

Go to top of page

Part 3: Determining the Diameter of a Completed 3 Sided Bowl

Determining the diameter of completed 3 sided bowl is rather difficult

because it cannot be easily measured. Moreover, that diameter often cannot be

determined theoretically because of breakage of a point or rounding of those points

during turning and/or sanding process. However, assuming that the distances between the

points is equal, they still form an equilateral triangle. Hence the ratios shown in

Figure 2 are still valid even though the value of s may not be.

Recall that in Figure 2,

the distance PC was called the circumradius which

is half the diameter of a circle circumscribed about the triangle. Observe

diameter of a completed bowl = 2 times the circumradius

= 2(s√6/3)

= 2s√6/3

Figure 2 shows the distance between the points of the bowl is

s√2.

diameter of a completed bowl 2s√6/3

---------------------------- = ------

distance between the points s√2

Solving for the diameter and simplifying the fraction and square roots, we see

diameter of a completed bowl = 2√3/3 times the distance between the points

= 1.1547 times the distance between the points

If the points are rounded, one can still determine the best center of the rounded corner and use this formula.

Go to top of page

Part 4: (Optional) 3 Sided Bowl Angles

This section discusses some additional properties of 3 side bowls - their angles. These results might be useful

when setting a cube to be turned or may be of interest to those who are just interested in the bowl's geometry.

We will be using some trigonometry - namely the tangent function. When I was in high school many years

ago, that topic was covered in a more advanced high school course but it is often covered at the end of a

geometry course now. So we are not really violating the statement in Part 1 that claimed that all the math used

in this page is normally covered or used in high school geometry. The following are two more basic geometric

principles that will be needed.

- Complimentary angles. Two angles are complimentary if the measures of those angles add

up to 90o. Figure 7a below shows the most common example. Angle

BAC is a right angle and angles

BAC is a right angle and angles

BAD and

BAD and

DAC are complimentary. Figure 7b

illustrates the second most common example of complimentary angles assuming the angle at

A is a right angle (90o).

It is known that the measures all three angles in a triangles in triangle add up to

180o. That means that the measures of angles at

B and C add up to

90o and the angles are complementary.

DAC are complimentary. Figure 7b

illustrates the second most common example of complimentary angles assuming the angle at

A is a right angle (90o).

It is known that the measures all three angles in a triangles in triangle add up to

180o. That means that the measures of angles at

B and C add up to

90o and the angles are complementary.

- Tangents. Note: Greek letters such as α,

β, and θ are normally

used for angles in trig instead of multi character names like

BAC or

BAC or

A.

A.

Consider the triangle in Figure 8. The tangent of an angle θ,

commonly written

tan θ; is defined as the ratio of the length of the opposite side to

the length of the adjacent side. That is,

tan θ = opp/adj

In this paper we will know the lengths of opp and adj sides

and will want to determine the angle θ. This is done with

the arctangent function commonly written as arctan or

tan-1. Thus,

tan-1(opp/adj) = θ

For example, suppose angle θ = 53.31o

tan θ = tan 53.31o = 1.5

The sides opp and adj might be 1.5 and 1,

3 and 2, or even 300

and 200, for example. And

tan-1 1.5 = tan-1 (3/2) = tan-1 (300/200) = 53.31o

If you have a scientific calculator and it is in the degree mode, you would generally press the

tan button

to calculate the tangent of an angle and a button such as INV or

2nd followed by the tan button in order

to calculate an arctan, the angle corresponding to the given ratio.

Now that we have the basic math needed, we can determine the important angles in a 3-sided bowl.

------

We want to find α1,

α2 and γ.

By looking at the figure, we observe that by symmetry the two

angles labeled α1 are equal justifying the labeling.

Lets first look at

α2. Triangle VAP is a right triangle so we

observe that

tan α2 = AP/VP

= (s√6/3)/(s√3/3)

= √2 = 1.4142135

after cancelling, rationalizing the denominator, and using some properties of square roots. We find

α2 = tan-1 1.4142135

and by using scientific calculator, we find

α2 = 54.74o

The calculation of α1

is almost the same except the denominator of the fraction is twice as big.

tan α1 = A'P'/VP'

= (s√6/3)/(2s√3/3)

= √2/2 = 0.7071067

Using tan-1, we determine

α1 = 35.26o

If we add the values for α2

and α1, we find the sum is

90o and the

angles are complementary!

Now that we have α2

and α1, we can find

β1 and

β2 easily.

Recall that triangle VAP is a right triangle so

α2 and

β1 are complimentary and their measures

add to 90o.

Likewise, triangle V'AP is also a right triangle so

α1

and β2 are also complimentary. Thus,

α2 + β1 = 90o α1 + β2 = 90o

Solving for the

βs, we obtain

β1 = 90o - α1 = 35.26o,

β2 = 90o - α2 = 54.74o.

Again, these angles add to 90o and are also

complementary and together from a right angle.

So γ = 90o. Thus the angle at the point of the 3

sided bowl is a right angle (assuming the turning and sanding process has not changed the angle). The

angle is a right angle of the original cube.

Go to top of page

Part 5: Using the Angle Analysis

to make a jig to cut corners from the cube.

(I plan to replace the photos in this part with ones that show a cube cut from a nicer piece of wood.)

If the math is over your, you can check out how to construct and use a jig if you click

here.

The α and β angles

found in the previous section, have an application that might be helpful

to some turners. Normally, when turning a 3 sided bowl,

the cube's opposites corners are placed in the lathe without any special attachments to center the cube.

But a few turners may want to turn it on centers using a drive center and 60 degree live center like they

would use to turn a spindle as shown on the right. In order to use

these attachments, one needs to cut off two corners of the cube, perpendicular to the axis of rotation. But

cutting those corners off precisely is quite difficult. In this section, we will discuss a way of doing this

taking advantage of the values found for those angles in the previous section.

In

http://www.armadillowoodworks.com/pdfs/three_sided_bowl.pdf, Craig Timmerman pictures a jig

he uses with a band saw to cut off corners of cubes but unfortunately, gives no details on

how it is built and used. Fortunately, we can use the angles found in the previous section to build and use a

different but simple jig

to cut corners of a cube on a table saw. The jig could be adapted to be used on a band saw or even

could be adapted to build a miter box and cut the corners by hand. First a look at the geometry.

Figure 10

Now, lets look at Figure 10. There are a couple of ways to interpret this figure. The first is that

it is similar to

Figure 9 except that vertex A' has been rotated

180o down into its actual position. That

means angle α1 points downwards instead of

upwards. A new construction line QQ' has been added. Right

triangle marks have been added at vertices V,

A, and Q and new angles

θ1,

θ2 and ω

have been specified.

Our goal is to determine angle θ1 which

turns out to be most useful with the jig.

In Part 4, the lines AP and AQ

were drawn perpendicular to line VV'. Also recall,

we showed that α2

and α1 are complimentary. That is, their

sum adds to 90o justifying the right angle mark at

vertex V. Likewise,

β1

and β2 are complimentary and vertex

A is also a right angle. We also showed

α2 = β2 and

α1 = β1.

Because α1 = β1,

right triangles VPA and QPV

are similar triangles. This means

θ2 = α2. The line

QQ' was constructed perpendicular to

VA' so

θ1 and

θ2 are also complimentary, their sum

adds to 90o so

ω is also a right angle.

This means that

θ1 = β1 = α1

= 35.26o.

Now lets look at figure 10 in second way. Set the cube so that vertex

V is the bottom, left, front corner of the cube and

V' is its top, right, back corner. Vertex

A' would be on the bottom below vertex

V'. Cut the cube diagonally along the plane formed by vertices

V, A' and

V' which is perpendicular to the bottom and at a

45o to the front of the cube. The result would be

what we see in Figure 10 although Figure 10 would have to be rotated counter clockwise by

an angle of α1.

Set the half cube on a table saw, perpendicular to the blade. If we tilt the blade by the

angle θ1 = 35.26o we see that it could cut a corner

of cube at an appropriate angle. What we need is to hold the whole cube at the

45o angle.

The jig

Even if the above analysis is over your head, you should be able to follow the construction of

the jig to cut the corners at the 45o angles.

A simple jig that does this shown in the left hand picture above. Piece of 2 by 4 has been

fastened to a thin sheet

of plywood panel at a 45o angle to the right side.

The right side is pushed along a rip fence. The panel and part of the 2 by 4 was cut about

8-1/2 inches wide with the blade set at a

set at a 35.26o angle. The corners are

cut with the blade at the same angle. The right

hand picture shows the

jig in use. (One corner of the cube has already been cut off.) The cube is placed in the jig as

shown and held in place by a second small piece of 2 by 4 clamped

to the longer fixed piece at location determined by the size of the cut corner and pushed pass

the turning blade.

The result is shown on the right. A corner was cut off. The corner has the shape of an

equilateral triangle which is accurate to best that can be measured. The photo also shows a

way to find the center of the triangle. The center of each side was marked and a line drawn

to the opposite corner. The lines meet at the center point.

Notes:

- The width of the bottom panel was designed to allow a 6 inch cube. However,

if one really plans to use cubes bigger than about 4-1/2 inches, consider using

2 by 6 pieces instead of 2 by 4 pieces and a wider bottom

board to simplify the clamping of larger blocks.

- The fixed

2 by 4 was cut at the angle shown to provide better support for the cube as it is cut and also

to provide a crude check that the blade is angled correctly.

- If a band saw is used, the same jig can be used but one would tilt the table instead of the

blade. Some way of supporting the jig such as a rip fence would be needed to keep the jig from

sliding off the table.

- If a band saw was used, the cuts were accurate enough and if planning as in Part 2 was used,

then the cube could be cut with the band saw in advance instead of having to use a parting tool as

suggested in that part.

- If one wants to cut the corners by hand, one could build a specialized miter box that would

hold the cube at a 45o. A slot would be needed

to cut the cube at the required angle.

Go to top of page

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dimensions of 3 Sided Bowl

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Length of side

|

Length of diagonal

|

Length between vertical points

|

Bowl radius*

|

Waist radius**

|

Bowl diameter

*

|

Waist diameter**

|

|

2 |

3.46 |

1.15 |

1.63 |

1.22 |

3.27 |

2.45 |

|

2.25 |

3.90 |

1.30 |

1.84 |

1.38 |

3.67 |

2.76 |

|

2.5 |

4.33 |

1.44 |

2.04 |

1.53 |

4.08 |

3.06 |

|

2.75 |

4.76 |

1.59 |

2.25 |

1.68 |

4.49 |

3.37 |

|

3 |

5.20 |

1.73 |

2.45 |

1.84 |

4.90 |

3.67 |

|

3.25 |

5.63 |

1.88 |

2.65 |

1.99 |

5.31 |

3.98 |

|

3.5 |

6.06 |

2.02 |

2.86 |

2.14 |

5.72 |

4.29 |

|

3.75 |

6.50 |

2.17 |

3.06 |

2.30 |

6.12 |

4.59 |

|

4 |

6.93 |

2.31 |

3.27 |

2.45 |

6.53 |

4.90 |

|

4.25 |

7.36 |

2.45 |

3.47 |

2.60 |

6.94 |

5.21 |

|

4.5 |

7.79 |

2.60 |

3.67 |

2.76 |

7.35 |

5.51 |

|

4.75 |

8.23 |

2.74 |

3.88 |

2.91 |

7.76 |

5.82 |

|

5 |

8.66 |

2.89 |

4.08 |

3.06 |

8.16 |

6.12 |

|

5.25 |

9.09 |

3.03 |

4.29 |

3.21 |

8.57 |

6.43 |

|

5.5 |

9.53 |

3.18 |

4.49 |

3.37 |

8.98 |

6.74 |

|

5.75 |

9.96 |

3.32 |

4.69 |

3.52 |

9.39 |

7.04 |

|

6 |

10.39 |

3.46 |

4.90 |

3.67 |

9.80 |

7.35 |

|

Item |

Formula |

Comment |

|

Length of side |

s |

Length of side of cube, VA |

|

Length between vertical points |

s√3/3 |

Length of AA' 1/3 of length of diagonal

VV' in diagram |

|

Bowl radius*

|

s√6/3

|

PA in diagram |

|

Bowl diameter* |

2s√6/3 |

Double of bowl radius |

|

Waist radius** |

s√6/4 |

ST in diagram |

|

Waist diameter** |

s√6/2 |

Double of waist radius |

* The Bowl radius and diameter are the theoretical diameter. In practice, because of

sanding, rounding corners, and other factors, it will always be smaller.

** The waist radius and diameter are the diameter in the middle where the left and right

slopes meet at point T.

Go to top of page

Maintained By: James Brink (brinkje@plu.edu).

BAC

BAC